What are the top transportation concerns as the suburban edge city of Tysons, Virginia turns itself into a more urban area? Here are two:

- Making all transportation forms easier and safer

- Improving livability with an urban mindset

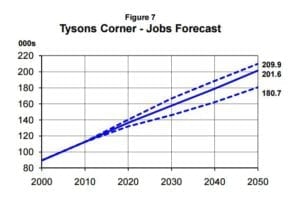

Population projections make these concerns all the more important. Even though Washington, DC regional growth has faltered in the recent past, long-range planning still projects major growth for Tysons by 2050: an office population that is slated to double and a residential population projected to grow from roughly 20,000 to around 100,000. While projections and estimates have varied over the years (and the graphic shown here is from an eight-year-old study), it is clear that, with the region promoting long-term growth, transportation will be a big factor in Tysons’ success.

Population projections make these concerns all the more important. Even though Washington, DC regional growth has faltered in the recent past, long-range planning still projects major growth for Tysons by 2050: an office population that is slated to double and a residential population projected to grow from roughly 20,000 to around 100,000. While projections and estimates have varied over the years (and the graphic shown here is from an eight-year-old study), it is clear that, with the region promoting long-term growth, transportation will be a big factor in Tysons’ success.

So is a proposed major roundabout at the intersection of Routes 123 and 7 (Leesburg Pike) – the crossing that gave Tysons its original “Tysons Corner” name – the solution that will address both these concerns?

A charrette in 2016 brought together regional stakeholders, transportation experts, and traffic engineers in the Washington DC region to determine not only whether a roundabout would address these concerns, but also the potential feasibility and benefits of four concepts that were presented to the participants. You can think of the charrette as a more traditional form of “pop-up urbanism,” although not quite as “guerrilla” as the Tactical Urbanist’s Guide to Materials and Design, which is worth a look for fans of urban living.

Improving Transportation: Better, Safer Traffic Flow

So Tysons could benefit from more efficient traffic flow. But, would a roundabout deliver those results? At 123 and Leesburg Pike of all places? It’s easy to roll one’s eyes at such a thought. Upon closer inspection, however, a roundabout in Tysons may not be such a bad idea.

Roundabouts: More Driver Options

Traffic engineers and transportation planners can quickly enumerate some of the advantages that a roundabout has over a traditional intersection, such as offering:

- a reduction in the severity and frequency of collisions due to reduced traffic speed,

- a simplified traffic pattern, both for drivers and pedestrians, and

- the ability to make U-turns within the normal flow of traffic.

Despite these and other benefits, the near-universal reaction in the United States to the news of a potential roundabout is dismay.

Nearly a decade ago, a report published in the Journal of the Transportation Research Board found that public support for roundabouts ranged from 22% to 44% prior to construction. Interestingly, a few years after construction, roundabouts were favored by 57% to 87% of the population. As drivers gain experience, roundabouts become more accepted, and the benefits accrue.

For those interested in how roundabouts operate, the Pennsylvania Department of Transportation recently published an informative four-minute video on how modern roundabouts work.

Tysons Roundabout: 4 Concepts

Please note: The two charrette design renderings shown here are by RK&K / Rhodeside & Harwell. For more information, click here.

Given these and other benefits, the Tysons Roundabout charrette participants broke into groups to consider four different design concepts, each with certain elements of a roundabout:

- A “Two Quadrant / Jug Handle” Concept (see image below) – a modified at-grade intersection that would be less costly to initially implement, since it would make use of current exit/entrance ramp roadways (the “jug handles”), and would utilize a system of adjacent grid streets to allow traffic to make its way through the four quadrants.

- An “Elevated Open Plaza Concept – featuring an elevated roundabout roadway above park areas at grade.

- An “Elevated Closed Plaza Concept” features a roundabout at grade with previous cloverleaf areas allocated to public park areas and a superstreet configuration below grade.

- The Cap Concept – the most elaborate plan. Designed to create a “signature” space for public gatherings, it would be larger than Dupont Circle in the District of Columbia. Routes 7 and 123 would be grade separated with a bridge through the middle of Route 7.

These potential reconfigurations of the Route 7/Route 123 interchange will be included in the draft amendment of the Tysons Comprehensive Plan along with a host of other additions and changes. After a lengthy year-plus-long review, this amendment will be heard by Fairfax County’s Planning Commission and Board of Supervisors in February-March 2017. If adopted, any reconfiguration of the interchange may be eligible for public funding.

While a roundabout could improve transportation flow at this busy intersection, rerouting of vehicular traffic doesn’t necessarily address the other concern: improving livability within an urbanizing area. In other words: allowing pedestrians and bicyclists to easily traverse the 7/123 intersection, and possibly allow for public spaces, like New York’s Central Park.

The Tysons Roundabout: An Opportunity for Urban Mobility

Transit is an important aspect of the Tysons redevelopment plan, which aims to transform the area from an “edge city with growing pains” into “America’s next great city.”

Yet, unfortunately, the most visible transit option in Tysons – Metrorail’s Silver Line – divides the area into two sections. This division creates wide street crossings, making navigation under the elevated tracks a barrier to the free flow of traffic – notably for pedestrians and bicycle riders who must hurry across the crosswalks. It’s not the ideal urban environment.

Ironically, in the one area where Metrorail does lie underground, the heavily traveled Routes 7 and 123 cross each other, making traversing this intersection nearly unthinkable for pedestrians and bicyclists.

New Street Design + Forward-Thinking Landscaping = Urbanized Livability

The underground Metrorail in this area presents a unique opportunity for transportation planners in Virginia and the Washington DC region to design infrastructure that both eases traffic and creates a truly livable urban environment: New Street Design + Forward-Thinking Landscaping = Urbanized Livability. Or, as Robert Steuteville of CNU Journal puts it, “build(ing) community through urban design.” The charrette participants were directed to consider multimodalism within each of the four design concepts. Several of these considerations are summarized here:

- “Two Quadrant / Jug Handle” Concept – in this concept, an elevated pedestrian bridge could connect two quadrants, with developable space in the two quadrants that are created by the existing vehicular on/off ramps. Public space uses include a museum, library, or programmable space. Although it takes pedestrian traffic into consideration, pedestrian circulation would be circuitous, and the public programming spaces would be divided between the two “jug handles” of the concept. What is unclear is what would happen to such spaces, and bike and pedestrian connectivity, once the jug handles were removed.

- “Elevated Open Plaza Concept (see image) – This concept includes an above-grade roundabout with traffic lights at grade. While beneficial for vehicular traffic, the concept was deemed to be too auto-centric and not conducive to pedestrians and bicyclists (who would be accommodated on the lower level), and thus was not recommended by charrette planners.

- “Elevated Closed Plaza Concept” – this design provides a “people-centric central gathering place” with a cap reachable via each of the four quadrants. It provides open public spaces for programming, public facilities, artwork, and recreation, providing more options for pedestrian movement, including access to the nearby Greensboro Metrorail Station. The roundabout would be at grade with the park land.

- Cap Concept – the most elaborate plan which is designed to create a “signature” space for public gatherings, this concept provides direct pedestrian access to Greensboro Station. It would essentially cap existing traffic conditions, with a circle for turns built as the third layer under the cap. With the large, public cap space on top of the vehicle roadways, it would create a large walkable, car-free environment. One downside: it’s potentially very expensive.

As you can see, there are many options to re-imagine and reconfigure the space at the 123/7 intersection. Many of those options will be needed to help Tysons manage higher density and create a more urban ethos. While costs are a consideration, so are the benefits, including how much to prioritize pedestrian and bicycle movement, and whether public, programmable spaces are important to fulfilling Tysons’ desire to be “America’s next great city.”

Please note: Charrette design renderings by RK&K / Rhodeside & Harwell. In addition to RK&K and Rhodeside & Harwell, charrette participants included regional government and transportation officials, homeowner groups, developers, corporations, and transportation consultants such as Wells + Associates.